Milla C. Svanøe Lund

By Rolf Svanoe, Decorah, Iowa

Let me tell you the story of a most amazing woman, my great grand aunt, Milla Svanøe. As a woman growing up in 19th century Norway, she overcame tremendous gender and role discrimination to pursue her dreams in a new country.

Milla was born Pernille Christense Svanøe on the 8th of September 1842 in Bergen, Norway. You can see her birth and baptism recorded at the Korskirken church in Bergen on the 9th of October that same year.

https://www.digitalarkivet.no/kb20070321670070

She was named after her paternal grandmother, Pernille Christensdatter Vold, who was a leader in the Hauge religious movement in the Stavanger area. In the early days of the movement, Hauge placed great emphasis on equality between men and women. Several women became leaders and lay preachers. Pernille joined the Haugean movement in 1799 and began preaching all over southern Norway. In 1809, she married Ole Gundersen Seglem, a close friend of Hauge’s and leader of the movement in the Stavanger area. Pernille died in 1821, well before the birth of the granddaughter who would later bear her name.

There is no doubt that Milla grew up in a home hearing stories of her grandmother. We don’t know why she never went by the name Pernille. Except for her confirmation record in 1859, all future records list her name as Milla, including the census records of 1865 and 1870.

https://www.digitalarkivet.no/kb20070323620663

https://www.digitalarkivet.no/census/person/pf01038249028064

https://www.digitalarkivet.no/census/person/pf01053362028162

Milla’s mother, Line Marie Seglem, died when Milla was only nine years old. Though the cause of death is not listed in the church records, it is possible it was due to complications with a pregnancy. Line was pregnant every two to three years and died at the age of 40 just two and a half years after her last child was born. The frustration at watching her mother die may have been one of the reasons she decided to go into medicine. Milla saw the toll that bearing eight children in seventeen years took on her mother. Perhaps this is one of the reasons she delayed marrying until later in life.

Milla was the only daughter in a family with seven brothers. No doubt, seeing the opportunities for education that her brothers had, inspired her to question traditional societal role expectations for women.

In 1862, when Milla was nineteen, her older brother, Peder Svanøe, traveled from Bergen to Chicago on board the brigantine named Sleipner. The Sleipner was owned by a group of businessmen in Bergen, including Peder and Milla’s father, Torger Svanøe. The arrival of the Sleipner in Chicago caused quite a stir as it was the first vessel from Europe to sail directly to Chicago. The hope was to begin a profitable trading relationship, delivering not only goods, but also passengers looking to start a new life in the US: One of those passengers in 1862 was Peder. Though there are no passenger lists from the Sleipner, we can assume that Peder was on board because he appears in the 1862 Chicago city directory. Peder soon became a prominent businessman in Chicago and by 1871 had been appointed as the Vice Consul for Sweden/Norway. There is no doubt that Peder wrote many letters home describing his life in Chicago. It was from him that Milla learned of an opportunity to further her education, an opportunity denied women in Norway.

In 1870 the Woman's Hospital Medical College of Chicago was organized. It was in close connection with the Chicago Hospital for Women and Children. For two years co-education of the sexes in medicine and surgery was tried. The male students found the experiment offensive and unanimously signed a protest against the policy. The result was the establishment of a separate school for women in 1870, with a faculty of sixteen professors. The requirements for graduation were fixed at four years of medical study, including three annual graded college terms of six months each. The first term opened in the autumn of 1870, with an attendance of twenty students.

We don’t know if Milla was part of that first term, but we do know that in 1874 she graduated from the Women’s Medical College of Chicago. Not only did she learn a new language, she learned a new profession. She was driven by her desire for knowledge to develop her talents and abilities so that she could help people.

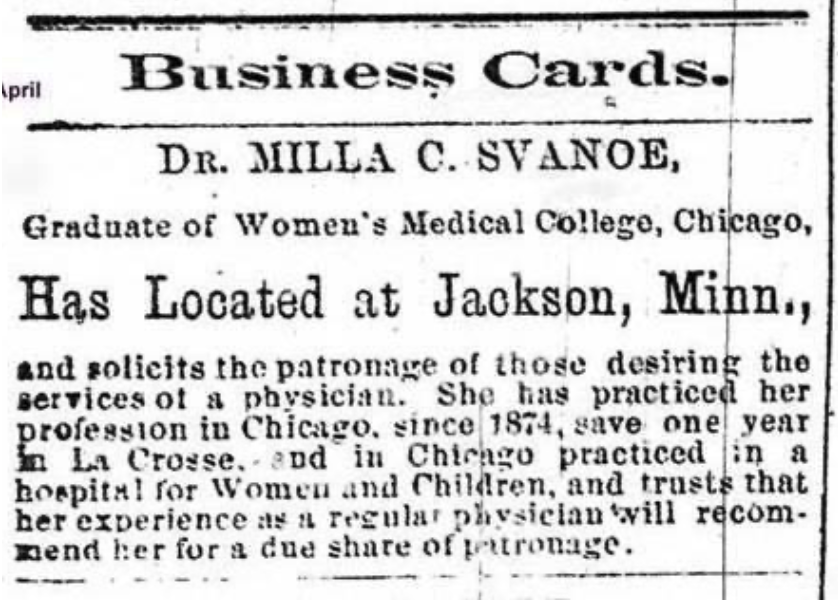

Milla practiced medicine in Chicago for a time. We are not sure how long exactly. She placed ads in newspapers to try to gain acceptance and patients. Ads for her services appear in newspapers in Chicago, Minneapolis and La Crosse, WI.

Milla appears in the 1880 US Federal Census in Jackson, Minnesota. When the local doctor left Jackson in March of 1880, Milla moved her practice there. She was the first female doctor in Jackson. She stayed just one year.

There is a photo of Milla’s office in Jackson. The photo is the oldest existing photo of Jackson, Minnesota. The sign on the front porch of the building (just above the standing man’s head) says, “Dr. Svanoe.”

A column in the local paper dated April 16, 1881, says,

“We regret to learn that Jackson’s skillful and accomplished lady physician, Dr. Milla Svanoe, is soon to depart—perhaps permanently—from this place. She has received a tempting offer from her brother of a through ticket for a visit with him to their native home in Norway.... She will carry with her the good wishes of scores of Jackson friends.”

Milla’s brother, Peder, had just married in Chicago to a Norwegian woman, and they no doubt were returning to Norway to visit and meet family.

Sometime in 1883-1884 Milla moved again, this time to Coos Bay, Oregon. Again, we see advertisements placed in local newspapers.

In May 1885, at the age of 42, Milla married William Lund, an Anglican priest from England. After their marriage she continued to advertise her medical services, now as Dr. Milla Svanoe Lund.

Marriage did not change Milla’s status as a physician. She continued to practice in Oregon until moving to Indiana in 1894.

One can only conjecture why Milla waited so long to marry. Until that time she had focused on building a career as a medical doctor. But the fact that she had failed to put down roots in any one place suggests that as a female doctor she was often met with prejudice, discrimination and hostility from male colleagues. Was she always looking for greener pastures, for the place where she was accepted and respected and her gifts were celebrated? Perhaps that is why she made the dramatic move to Oregon. Would life be different there? Would people accept her as a physician? Was marriage finally giving in to the reality of discrimination that she had faced her whole life. There is no doubt that in William Lund, Milla found a partner who was not threatened by her gifts, who could celebrate her talents and allow her freedom from traditional marriage role models.

There are no surviving letters written by Milla describing her life or the challenges she faced. We know little other than the outline of events of her life. But there is much that we can surmise from the conditions that other women faced at that time.

“Women’s contributions to medicine have been monumental — and will continue as their ranks increase in the ensuing decades. This, and the awareness Women’s History Month brings, are vital. Many of the female pioneers in medicine focused their efforts on areas such as midwifery, gynecology, and breast and uterine cancers — issues that affected women. Without the contributions of these pioneering women and those who came after them, women’s health care would not be what it is today.”

“The impact of how women physicians practice medicine and interact with their patients cannot be understated. Compared with their male counterparts, women physicians may be more likely to adhere to guidelines, provide preventative care, provide more psychosocial counseling, and spend more time with patients.11 Challenges, however, persist. Women in medicine still face gender bias, lack of recognition, and salary inequality. Awareness of women’s accomplishments and challenges is one way to try to improve the lives of women in medicine.”

https://www.clinicaladvisor.com/features/history-of-women-in-medicine/

Many people did not think women should be doctors at all. A medical professor at Harvard University in Boston, Massachusetts, wrote a book claiming that education for women would ruin their health and make them unable to have children. In some places the men in charge of licensing doctors refused to give women doctors licenses. Women were often barred from medical societies.

https://www.iowapbs.org/iowapathways/mypath/2647/doctors-wanted-women-need-not-apply

Women Physicians and the Cultures of Medicine, edited by Ellen S. More, Elizabeth Fee, and Manon Parry, comprises 12 essays, all but one written by women, that examine the wide-ranging experiences of women physicians in the United States, shedding light on their accomplishments and struggles from the mid-19th century to the present.

The first section, “Performing Gender, Being a Woman Physician,” focuses on the overwhelming challenges faced by the first generations of women physicians entering the male-dominated field of medicine. Many spent a substantial part of their careers trying to convince others that there were no biological or intellectual barriers that should prevent women from practicing medicine. Mary Putnam Jacobi conducted a substantial amount of clinical research in the late 19th century that she hoped would prove that biological functions such as menstruation and childbearing were not obstacles for women wanting to enter traditionally male-dominated professions. Marie Zakrzewska, one of the most accomplished medical practitioners and educators of the 19th century, insisted that men and women did not differ anatomically or psychologically in any significant way (although she modified her position late in her career.)

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2673877/

https://www.jstor.org/stable/3787412

After marriage Milla seems to have followed her husband’s career path. Wherever they went she continued to practice medicine. Rev. Lund served a church in Indiana and later a mission in Jamaica. Finally, they moved to Jacksonville, Florida. We have a record of Milla on a 1904 passenger list returning to Florida after a visit to Norway. She was no doubt on the island of Svanøy for the 100th Anniversary Jubilee celebrating the purchase of the island by her grandfather, Ole Helling Svanøe. Ole was a prominent farmer and politician, and a leader in the Haugean movement and close friend of Hans Nielsen Hauge. The island had been purchased with Hauge’s financial help in order to bring a religious and economic boost to that part of the country. Ole also became a Stortingsmann, a member of the Norwegian parliament, and served several terms.

Milla returned to Bergen, Norway in 1905 after the death of her father, Torger. She is listed as one of the heirs in her father’s probate record. Tragically, Milla died soon thereafter on March 8, 1906 in Florida. She is buried at the Evergreen Cemetery in Jacksonville. The cemetery records list the cause of death as surgical shock. Perhaps there is a bit of irony in her fate that someone so devoted to the surgical arts should herself die on the surgeon’s table.

It is often the children who preserve the memory and photos of their parents. Milla had no children to pass along the stories of a remarkable life. Hers was a life that should be remembered and celebrated for what she accomplished. She was one of the first women physicians in the United States. She is certainly the first Norwegian woman to get a degree as a physician. Perhaps this short story can be means to remember a most remarkable woman.

Cover Image: The 100th Anniversary photo of the family on Svanøy.

get updates on email

*We’ll never share your details.

Join Our Newsletter

Get a weekly selection of curated articles from our editorial team.

.svg)